The #gamergate protest started as a result of evidence hinting that many sources among games media were colluding together behind the scenes to promote their own agenda. The most obvious piece of the puzzle was a series of articles, all posted on the same day, giving a false description of gamers that was apparently intended to be derogatory, declaring their interests unimportant to either media or creators in the gaming industry, and insisting that they as media are entitled to continue their bad habits with impunity. This is what we in the parenting industry affectionately refer to as a temper tantrum, and a particularly foolish one at that. It flies in the face of logic for any industry that markets a product to consumers and would be a red flag to any rational reader. As I explained in my previous post, the media’s product is information. As a distributor, it’s their job to ensure that they’re providing a product that suits their consumer’s needs. In other words, factual information that you actually want, not promotional advertising thinly disguised as news.

The protest made it very clear that the consumer was not satisfied with the product. Outlets that had published articles ringing the death toll of the gamer as the industry’s focus saw drops in activity on their sites as readers abandoned them for more credible sources of information, and more interesting discussion. Some have seen a loss in revenue as advertisers, in response to widely expressed consumer outrage, pulled their support from the sites. Some media sources, realizing they actually need their readers, have responded by striving to improve their policy to provide greater transparency in respect to any potential conflict of interest between journalists and industry personnel.

Others have continued the tantrum, or picked it up and tried to amplify it.

The excuse for this seems to consistently be that their political ideology makes this particular conflict of interest acceptable, and don’t you dare disagree, you pale-skinned, hairy-faced misogynists!

In support of this, various articles have attempted to shift the discussion from criticism of the bias, the conflict of interest, and the manipulation back onto gamers by labeling rejection of their push to infuse their ideology into an apolitical, recreational activity “misogyny.” The stated reasoning, as it is recently described in this Mirror article, is that because the particular ideological push being rejected is feminism, gamers must hate women.

This tactic is also known as a DARVO attack: Deny, Accuse, Reverse Victim and Offender. You can read more about that specific behavior here. In this case, we have obstinately biased media screaming from the pulpit of their outlets, long-winded versions of, “We didn’t lie to you! You’re just hateful, inferior people!”

This particular attack is rooted in layers of presumed entitlement.

The base is the belief that women are exempt from criticism, and therefore any claim made on behalf of women is also exempt. This is a flawed approach to women’s issues, based on the false assumption that women are all in agreement, and always right. It’s an attitude that is inherently sexist, because it depends on an inequality; the assignment of so much greater relevance and legitimacy to women’s interests that women are entitled to acquiescence of other interests when there is a conflict.

The second layer is the treatment of “feminism” and “women” as interchangeable terms, making women the territory of feminism and inferring upon feminism that same presumed exemption from criticism. There has been plenty of evidence to the contrary, including #womenagainstfeminism on twitter, on tumblr, and on facebook, and as part of the #gamergate protest there’s #notyourshield, the response of female and minority gamers to being told that social justice whining represents their interests. It seems that many, many women are averse to feminism’s territorial claims. Apparently we’re not all so much in agreement as is believed.

Feminists don’t get it, however, and treat women’s refusal to bow to their presumed authority over all things female as a form of apostasy, which leads to the third and fourth layers, too intertwined to separate.

These are self-assigned moral superiority, and the belief that said superiority infers a right to impose one’s ideology on others. Essentially this is the attitude of aggressive evangelism; the belief that one need not recognize other people’s independence because one believes that one is right. Not simply content with the ability to exchange ideas with others in an intellectual setting, the individual feels entitled to impose his or her ideological standards on the greater community “for their own good.” To the individual presuming this entitlement, opposition to his or her attempt at influencing your beliefs is not merely criticism or disagreement, but blasphemy, justifying behavior he or she would otherwise recognize as abusive, such as misleading or bullying others.

The fifth is that the gaming community is going to give a shit about this approach, as if accusations of blasphemy and apostasy are an effective response to dissent against the ideological push. In communities with more rigid social structures and existing loyalty to the belief system, such castigation is effective. This is not that kind of community, and as a result the accusations simply look ridiculous to the accused. Unable to see past their own beliefs, however, feminists in media have failed to understand that, and the barrage of accusations continues.

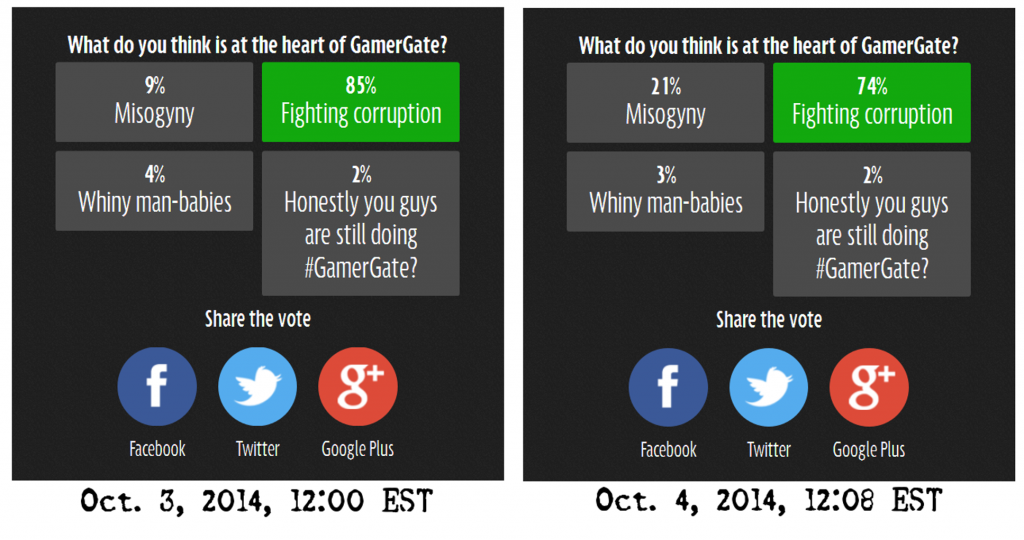

And they continue to be ineffective, at least according to the continued response at #gamergate, #notyourshield, and other discussions on the topic… including the survey at the bottom of that Mirror article, the results of which do not reflect the article’s conclusion.

If you like what you read, please consider becoming Hannah Wallen’s patron. The Brigade runs on donations by readers like you.

- REMINDER: Badger Meetups in August and September! - August 15, 2025

- Lilith, feminism’s perfect icon? - August 15, 2025

- Badger Meetups in August and September! - July 8, 2025